By Bruce Davie and Amar Padmanabhan

From the beginning of the Magma project, it was clear to those of us on the Technical Advisory Committee that to easily and efficiently connect new user communities, we needed to reduce the complexity of managing and operating a mobile core network. One of the established technologies that we chose to achieve this goal was a control plane based on SDN (software-defined networking). This approach turns out to be a significant change to the way control planes have traditionally been built for telecommunications. To see why, we need to look at the relationship between control and data planes.

The idea that the data plane and control plane can and should be separated is almost as old as networking. From the earliest days of the internet, the data plane was defined independent of the control plane and (aside from IPv6) has barely changed since. Meanwhile, the control plane has continued to evolve largely independently, with numerous new routing protocols added over time.

SDN has been the most successful effort to formalize the separation of the internet’s data and control planes. While the original architecture separated control and data conceptually, SDN enabled separation into different physical devices, with protocols (e.g., OpenFlow) allowing communication between these planes.

Separation in the telecom network

Control and user plane separation is a fundamental part of the telecom network as well. SS7, for example, forms part of the control plane of the telephone network and is largely independent of the user plane. As with SDN, CUPS (Control and User Plane Separation) was intended to allow different devices to host each plane. However, there are some important differences in how control planes are implemented in typical 3GPP systems versus how SDN systems implement them. Magma takes an SDN approach to building a mobile packet core, and it’s worth taking a step back to understand why.

One of the main objectives behind Magma is to deliver a mobile core that can be managed cost-effectively and with high scalability. SDN was successful not only because it provides a clear point of separation between control and data planes, but also because it introduces a central point of control. This is true for Magma as well.

Consider three applications of SDN:

- Traffic engineering (as in Google’s B4) needs a central view of traffic demands to achieve optimal path placement.

- Network virtualization (as pioneered by Nicira) needs a central API so that networks can be provisioned and managed by other software without knowing where all the network components are located.

- SD-WAN needs a way to manage a network as a whole rather than provisioning individual boxes, branches, and tunnels.

In the same way, if mobile and wireless networks are to be managed efficiently at scale, we need centralized management for configuration and monitoring, and central APIs to integrate with other software systems. All of these capabilities come when we build a centralized control plane.

The power of centralized management

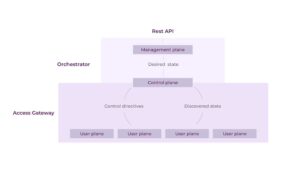

Consider the figure below of Magma’s SDN-based system. The management plane sits above the control plane and provides a single point of entry for configuration and status information, such as metrics and alerts. Configuration information is provided to the management plane via the northbound API to update the desired state. This centralized management model makes it possible to provide a single API to manage an entire network, rather than managing a series of boxes one by one, greatly simplifying the operation of the mobile core network. It also provides an API for integration with other software systems for logging, alerts, metrics, and more.

Magma applies SDN to management, control, and user planes.

Note the “desired state” model shown here. It’s a common pattern in cloud-native systems. The control plane’s main job is to continuously reconcile the actual state of the system with the desired state in the face of configuration changes, failures of components, or other events, such as the arrival and roaming of user equipment (UE) like smartphones.

Centralized and distributed components

Note that this is a logical view of the architecture, not a physical one. The control plane is logically centralized in the diagram, but it is actually implemented in a hierarchical and distributed manner for availability, fault isolation, and scale. Some parts of the control plane run centrally (in the orchestrator), while others are distributed to the access gateways, so they are close to the distributed user plane and scale out accordingly. This is another SDN design pattern: a hierarchical control plane that combines a centralized component and a distributed component.

Open Virtual Network (OVN) is another example of an SDN system built with this approach. This hierarchy provides scaling and reliability benefits while retaining the centralized management that’s essential for simplified operations and integration with other systems via a central, network-wide API.

SDN-based control planes save us from having to continually reinvent techniques to achieve reliability, fault tolerance, and scalability in every network protocol. SDN leverages well-known distributed systems techniques and, in many cases, existing, proven implementations to deliver those properties. This paves the way for adding new capabilities (such as traffic engineering) without having to repeatedly solve problems like reliable dissemination of state among all the network components.

Separation of control and data alone is not enough

In telecom networks, the control plane often refers to signaling protocols used to set up the user plane channel. For example, before a UE (like a smartphone) can start exchanging data with the internet, it needs to authenticate itself, a user profile needs to be looked up, and the device needs to be assigned an IP address. All of these are control plane functions. Once they are complete, the UE can send and receive data via the user plane. If the UE roams to a different base station, more signaling needs to take place to set up the user plane state so the UE can send and receive data via the new base station.

Separation of the user plane and control plane

Under the formal definition of CUPS, some devices may be dedicated to user plane functions (e.g., moving packets between a UE and the internet) while others may be dedicated to control plane functions (e.g., authentication of UEs). This separation is a helpful principle for building a network, but it does not, on its own, deliver the benefits of SDN. These benefits come from a more expansive view of the control plane.

SDN makes the control plane more useful

The centralization of the SDN control plane is what enables an operator to manage a network as a whole, rather than on a box-by-box basis. The creators of SDN realized that only by centralizing the control plane would it become easier to manage and reason about the behavior of networks. For example, troubleshooting now starts with querying a central API rather than trying to figure out which boxes to investigate. A configuration change that touches many devices can be expressed centrally as a change to the desired state of the network; the control plane then determines how to configure the appropriate set of devices.

Note that the control plane is constantly gathering information from the user plane, such as learning about the new location of a UE. This is the “discovered state.” When there is a discrepancy between the discovered state and the desired state, the control plane is responsible for deciding how to resolve that discrepancy—for example, by pushing new information to a certain part of the user plane. In these cases, the control plane is about much more than signaling: it’s constantly responding to changes in the network, including topology changes and component failures.

SDN transformed networking because it enabled completely new operational paradigms. But separation of control and data was only the first step. It was the development of logically centralized control planes, using distributed implementation to achieve reliability and scale, that made SDN successful. By going beyond the CUPS model to deliver the benefits of SDN to mobile networks, Magma can help mobile operators build scalable, resilient systems with simplified operations and the power of network-wide management.